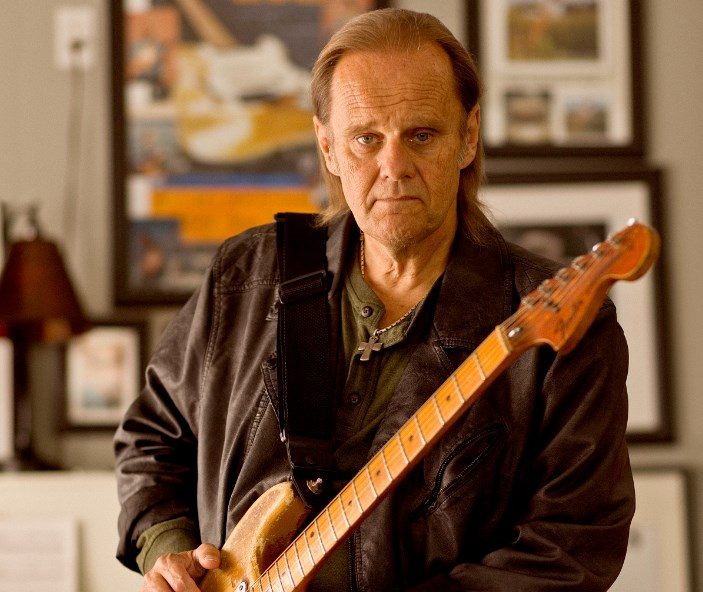

If you've had the pleasure of listening to ‘Battle Scars', the exceptional new album from charismatic blues guitarist Walter Trout, you'll know it's an incredibly honest, unsettling and ultimately inspiring account of how a life-saving liver transplant brought him back from the brink. During his recent UK tour we caught up with Walter to discuss the record and learned how a brush with a higher power has forever changed him.

How's your health holding up now you're back on the road?

I feel good. Band's playing great. I'm kind of like a reborn person here.

We can hear that on ‘Battle Scars'. Was making it cathartic or difficult?

I did it as therapy. It was like the equivalent of talking to a shrink and trying to get some stuff out about what happened to me and my wife and family. It happened so quickly. I wrote six of those songs in half a day. A lot of times with lyrics you go over and over them, you change it, worry about it, lay awake at night going over one line. On this one it just came out. The final result I'm really, really pleased with.

The energy and passion the songs are played with gives them a life-affirming subtext.

Well I'm joyous, man. I made it through. I'm singing about some pretty graphic, dark stuff on there, but I made it through and I think that that's what the music says.

There are, understandably, many nods to God, the devil and faith.

Well, I've always had a strong belief in a higher power. I don't think it's a big man sitting in the sky in a fucking chair, but I do believe there's a power we don't understand. It's worked very visibly in my life and given me messages and revelations. When I was with John Mayall, I had a revelation and went to him and said: “Last night I had this major flash that if I would show the higher power the strength to give up drugs and drinking, take my gift seriously, become a sincere person and not a drunk, doped out idiot, use my music, try to use it for good, that I would be given the desires of my heart.” And John said: “Well then you better go for it.”

And so I quit drinking, drugging, and thought the desire of my heart was going to be I'd become the next Jimi Hendrix or some shit. But it wasn't. Right after that I met my wife, the love of my life, and was given a family, which I never had. I came from a severely dysfunctional, abusive youth and I was given a beautiful family. Something like that happens, you can't ignore it. You can't say: "Oh, this is coincidence." And there's been a few of those in my life that I won't go into. So I've had some sort of power that has worked in my life and is still working in my life. The Native Americans call it the great spirit and to me that's a perfect definition. It's something we can't comprehend. But Fly Away is about an experience I had where I think I saw the other side. I think I saw what's next.

Can you explain what you saw?

I laid in bed awake, and it was dark in the room. This actually happened in my house before I was hospitalised, so I was definitely not on fucking hospital drugs. There were little balls of white light flying over my head and suddenly I was out of my body and with them. I could see myself in the bed, and I was separate and had no physical presence, no weight, no carnal desires, no pain. I had no space, no time and it was just pure consciousness and blissful in a way that I could never ever explain to anybody. And we communicated, we flew and were in the universe, and they said: “You can come with us now. You wanna come, let's go.” And I knew that meant I would die. I said: “I wanna watch my children grow up.” And they said: “OK, we'll see you sometime soon.” And, boom, I was back in my body.

There's certain people who I talk to that are atheists and they say: “Oh, it's a hallucination.” I go: “No, it was real.” You can say what you want, I know what I experienced and I know how it changed me. It altered my perception of life profoundly. Priorities were massively rearranged. Things like: “Why does this guy sell more records than me?” Instantaneously, I just didn't give a shit any more about that kind of stuff.

Were you ever close to giving up?

I really thought I saw the other side but I certainly didn't wanna die. There were times I told my wife: “I'm ready to die because I'm in so much pain and I've had a good life and I've got great kids. I wanted to be a musician, it was my childhood dream. I'm leaving behind 22 albums under my own name and I've been on, I think, 42 albums total. I lived the dream, just let me go." And she said: “No, you can't go.”

Tell me about Gonna Live Again.

That is a conversation with that power, saying: “OK, you've given me this other chance.” In hospital, in one day three people died right around me and I'm like: “How come I've come through this? What's my responsibility? What do you expect of me?” And I think I find the answer in the song: be a better man, a better husband, father, musician. Try to live as generous, honest, truthful, honourable life as I can.

Omaha recalls those around you in the hospital not making it. Do you have any survivor's guilt?

Well, that's partly in that song. I say I've lied, cheated, done people wrong. I've done a lot of things in my life I'm not proud of, especially back in my dope days. When you're addicted to drugs, you gotta have your drugs. People are secondary and you hurt a lot of people that love you. I hurt my mother. Thank God I got sober before she passed so she was able to see me come out of it. But when I'm her dear son and we're so close and she says, “I have resigned myself to the fact that you're going to die of drugs very soon and I'm ready for it to happen.”, you realise what incredible pain you have inflicted on somebody.

Tomorrow Seems So Far Away says to survive, someone else will have to give it all. How do you wrap your head around knowing that for you to live, someone has to die?

Well, that's something I grappled with and I came to the conclusion that, somebody, they've died. It's nothing I had anything to do with, but they have done something beautiful. Not just for me, but if they're a donor, there's eight different organs they can donate. That means, potentially, they've saved eight people's lives. You do, in your head, go through that thing of: “Somebody has to die to save me.” But they're gonna die whether they save me or not. Their time is up and that's just how it is.

People who don't know about transplants assume someone gets a new organ and they're fine, but your recovery was extremely gruelling.

When you go in they gave you this myth: “Man, after you get your transplant you wake up and you feel great because suddenly your body's working again.” No, I got worse after it. You've been through a major trauma if you think about it. You're sliced open, completely across your abdomen from side to side, to have a huge organ ripped out of your body and they stick another one in there and staple you back up. You've been through some pretty tough shit there. You just have to go through the recovery period. I did have brain damage. I did take speech therapy. You've got to go to physical therapy. Your job is to get yourself going again, to work out, exercise. For me, to practice the guitar, to practice talking, walking. And now, I haven't felt this good in so long.

How did it feel the first time you picked up the guitar and sounded like Walter Trout?

Awesome, but that took a long time. I couldn't play at all, I had to start over. I had to retrain the muscles and retrain the brain to send the signal to the muscles. When I first picked it up it was horrible. I said to my wife: “Did I ever really do this?” My fingers were like on fire. I'm like: “How the fuck does anybody ever do this?” I had no calluses, I had no strength. But I worked with weights, I kept practising four or five hours a day and it came back. But it took me 13 months from the transplant until I felt good enough to get on a stage. That was the Royal Albert Hall gig.

I imagine that was an incredible feeling?

That was mind blowing. Anybody else would go down to the local pub, see how it goes. Me? I go: “What the hell, I always wanted to live on the edge. Lets' try it, Royal Albert Hall, here we go.” And it was awesome.

What was it like the first time you played with your band again?

It was incredible. It was joyous and still is. I feel like I've started over. It's like when you're 15 and you're in a garage jamming with your friends, that high where you're not even thinking about if this is going to be a career. You're just buzzed from the experience. That's what it's like again.

How does it feel when you step out on stage and see the love the audience has for you?

It's hard to explain. I walk out, I get a huge ovation. Part of it's just because they're happy I'm still alive. I know that. But then when the band kicks in and we start really blazing it's beautiful.

Now you've got this album off your chest, what's next?

I'm gonna do a live album on this tour and that'll come out next year. And after that I'll worry about writing some more stuff and see what comes out. But this was like giving birth to a child and I'm gonna let that kid grow for a little while before I think about having another kid.

'Battle Scars' is out now on Mascot.

NOTE FROM THE EDITOR

We don't run any advertising! Our editorial content is solely funded by lovely people like yourself using Stereoboard's listings when buying tickets for live events. To keep supporting us, next time you're looking for concert, festival, sport or theatre tickets, please search for "Stereoboard". It costs you nothing, you may find a better price than the usual outlets, and save yourself from waiting in an endless queue on Friday mornings as we list ALL available sellers!

Let Us Know Your Thoughts

Related News

No related news to show

|